Show summary Hide summary

- Juvenile dinosaurs at the core of the Jurassic food web

- Dinosaur growth, vulnerability and energy flow

- From Jurassic baby prey to Cretaceous super‑predators

- What this means for dinosaur development and modern science

- How did researchers know juvenile sauropods were common prey?

- Does this study prove that baby dinosaurs caused predators to evolve in a certain way?

- Why were sauropod eggs and hatchlings so small compared to adults?

- Is the Dry Mesa food web representative of the whole Morrison Formation?

- Where can readers find more technical information on Jurassic ecosystem modelling?

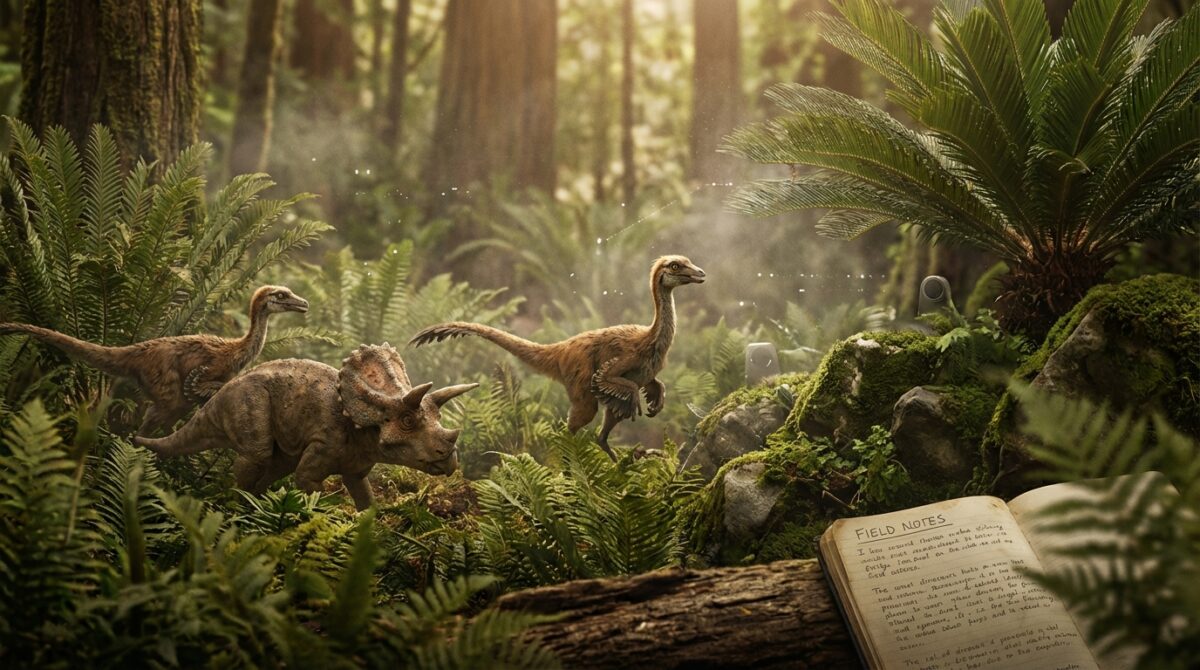

What if the Jurassic’s biggest predators lived off the tiniest giants? New research suggests that juvenile dinosaurs, especially baby sauropods, quietly carried much of the Late Jurassic Ecosystem on their fragile backs, feeding carnivores and shaping who survived.

A team led by University College London (UCL) has now shown that very young sauropods were not just occasional snacks but a central energy source for meat-eating dinosaurs. This work, published in the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin, turns baby long‑necked dinosaurs into key players in ecosystem dynamics, not background victims.

Juvenile dinosaurs at the core of the Jurassic food web

The headline finding is stark: in this Late Jurassic community, juvenile sauropods were a major, routine prey resource for several predator species. The study focused on fossils from the famous Morrison Formation, roughly 150 million years old, and especially the Dry Mesa Dinosaur Quarry in Colorado, where bones from at least six sauropod species lie mixed with predators and plants.

A Groundbreaking Quantum Mechanics Book Uncovers a Monumental Insight

The Bold Hypothesis That Time Is an Illusion—and How We Might Demonstrate It

Lead researcher Dr Cassius Morrison (UCL Earth Sciences) and colleagues from the UK, United States, Canada and the Netherlands reconstructed who ate whom using a mix of fossil evidence and modern ecological modelling. Their conclusion aligns with earlier hints that baby dinosaurs functioned almost like “fast food” for predators, but now quantified at the scale of an entire community.

How scientists rebuilt a Jurassic ecosystem from stone

The method can be summed up in one sentence: the team combined fossil anatomy, tooth wear, chemical signatures and rare stomach contents to feed into software that maps out feeding links. In practice, this meant using body size estimates, bite mechanics, dental microwear patterns and stable isotope ratios from bones and teeth to infer likely predator–prey and plant–herbivore connections.

These data came mainly from Dry Mesa, a quarry capturing up to about 10,000 years of deposits within the broader Morrison Formation, a Mesozoic Era rock unit that spans around 1.5 million square kilometres in western North America. With this input, the team ran models similar to those used for living ecosystems, producing a highly resolved food web that sits alongside other influential work such as “The influence of juvenile dinosaurs on community structure and diversity”.

Dinosaur growth, vulnerability and energy flow

The most striking contrast highlighted by the study lies in dinosaur growth patterns. Sauropods such as Diplodocus, Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus grew to lengths beyond a blue whale, yet their eggs measured only about 30 centimetres across. That gap between tiny hatchling and multi‑tonne adult created a long window of vulnerability.

Evidence from nest structure, egg size and trackways suggests that young sauropods behaved more like baby sea turtles than like protected mammal calves. After hatching, they were probably left to fend for themselves in landscapes teeming with predators such as Allosaurus and Torvosaurus. In this scenario, mortality among the smallest age classes would have been extremely high, funnelling a large share of plant energy into carnivores via these exposed juveniles.

Why sauropods dominated Jurassic ecosystem dynamics

When the researchers compared different herbivore groups, sauropods emerged as the main hubs of the food web. They connected to more plant species than ornithischians like Stegosaurus, and they also linked to more predators. Ornithischians carried armour and spines, making them riskier targets, while slender‑limbed young sauropods offered easier returns for hungry hunters.

This centrality means sauropods shaped ecological roles across the community. Predator numbers, body sizes and hunting strategies would all have been constrained by how many juvenile sauropods the environment could supply. The study suggests that Late Jurassic apex predators might have relied far less on tackling fully grown, dangerous prey than their Cretaceous counterparts.

From Jurassic baby prey to Cretaceous super‑predators

The Dry Mesa web also helps explain why later predators, such as Tyrannosaurus rex, evolved such extreme traits. Roughly 70 million years after the Morrison ecosystems, sauropods were less abundant in many regions. Large theropods could no longer count on a constant stream of easy juvenile sauropod meals.

This shift may have created selection pressures for stronger bite forces, sturdier skulls and more refined vision. T. rex and close relatives targeted heavily armed animals such as horned Triceratops, a very different business model from Allosaurus feeding in a nursery‑rich Jurassic floodplain. Independent evidence from a 75‑million‑year‑old juvenile tyrannosaur with preserved stomach contents supports the idea that young predators also tracked smaller, agile prey, indicating complex shifts in dinosaur behavior through time.

Injured hunters and the safety net of baby prey

Co-author William Hart (Hofstra University) pointed to another consequence of abundant juveniles. Some Allosaurus skeletons preserve serious, even gruesome injuries—broken ribs, crushed vertebrae, damage possibly from Stegosaurus tail spikes. Yet some individuals survived long enough for bones to heal.

Why did those wounded hunters persist? A landscape scattered with small, undefended sauropods offers a plausible answer. Predators did not need to risk combat with armoured adults every time they fed. Easy juvenile prey may have acted as an ecological safety net, letting injured carnivores recover and keeping large predators in the system longer.

What this means for dinosaur development and modern science

Beyond one quarry, the study reframes how dinosaur development and ontogeny shaped communities. Because all dinosaurs hatched small, their early growth stages occupied feeding niches that sometimes overlapped with those of entirely different species. Work on ontogenetic niche shifts, including analyses archived in resources like NSF‑supported ecosystem models, shows that this pattern could suppress the need for many mid‑sized carnivore species.

For modern ecologists and conservation planners, the message is familiar: who eats the babies matters. In today’s ecosystems, high predation on young herbivores can stabilise vegetation and control predator numbers. The Morrison Formation demonstrates that this principle already operated 150 million years ago, under very different climate and plant communities.

- Juvenile Dinosaurs acted as key energy conduits from plants to predators.

- Ontogenetic shifts in diet and size restructured ecosystem dynamics.

- Sauropod life histories influenced predator injuries, survival and diversity.

- Comparing Jurassic and Cretaceous systems clarifies long‑term evolutionary pressures.

There are, however, clear limits. The food web reconstruction rests on fossils from a single quarry and a narrow time slice within the broader Morrison Formation. Sample sizes for some species are modest, and tooth wear or isotope data can only approximate diets, not capture every seasonal or regional variation. The authors carefully avoid claiming direct causation for specific evolutionary changes, instead proposing plausible links between prey availability and predator traits that future studies can test.

How did researchers know juvenile sauropods were common prey?

They combined several lines of evidence from the fossil record: the relative abundance of small sauropod bones, bite marks, dental microwear of predators, chemical isotope data and rare stomach contents. These indicators, modelled together, showed that very young sauropods fit the size and vulnerability profile of frequent prey in this Jurassic ecosystem.

Does this study prove that baby dinosaurs caused predators to evolve in a certain way?

The study does not prove direct causation. It shows strong correlations between the availability of juvenile sauropods and the structure of the food web. The authors suggest that easy access to young prey likely influenced predator evolution, but they frame this as a hypothesis consistent with broader paleontology research, not as a definitive cause‑and‑effect result.

Why were sauropod eggs and hatchlings so small compared to adults?

All known dinosaurs laid eggs, which physically limited egg size because of shell strength and gas exchange. As a result, even giant sauropods started life at under 15 kilograms. Long, rapid growth phases then bridged the gap from tiny hatchling to multi‑tonne adult, creating a prolonged stage when juveniles were small, fast growing and exposed to predators.

Is the Dry Mesa food web representative of the whole Morrison Formation?

Tiny Mammals Sound Alarms: Scientists Unlock Their Hidden Warning Signals

This Spider’s ‘Pearl Necklace’ Turns Out to Be Living Parasites

Dry Mesa offers an unusually rich, well‑studied snapshot of one part of the Morrison ecosystem over roughly 10,000 years. It provides strong local detail, but conditions elsewhere in the formation could have differed. The authors treat it as a detailed case study and encourage comparisons with other sites to see how general these patterns of juvenile predation were.

Where can readers find more technical information on Jurassic ecosystem modelling?

Readers interested in deeper technical detail can consult peer‑reviewed work on dinosaur community structure, such as articles indexed on PubMed or Science, and institutional summaries like the UCL news piece on baby dinosaurs as common prey. These sources provide model parameters, statistical approaches and confidence intervals for the reconstructions discussed here.