Show summary Hide summary

Your everyday experience of a solid, stable world hides a quiet puzzle: if matter is fuzzy and probabilistic at the quantum scale, why do your eyes and instruments almost always agree about what is “really” there? A new theoretical discovery offers a novel approach to this shared reality, using tools that also power cutting‑edge quantum technologies.

Discovering how shared reality emerges from quantum fuzziness

At the heart of the puzzle lies a clash between quantum rules and common sense. Quantum theory says that a single atom can exist in many possible states at once, only settling into a definite outcome when measured. Human perception, by contrast, reports coffee cups, keyboards and city streets with reassuring clarity.

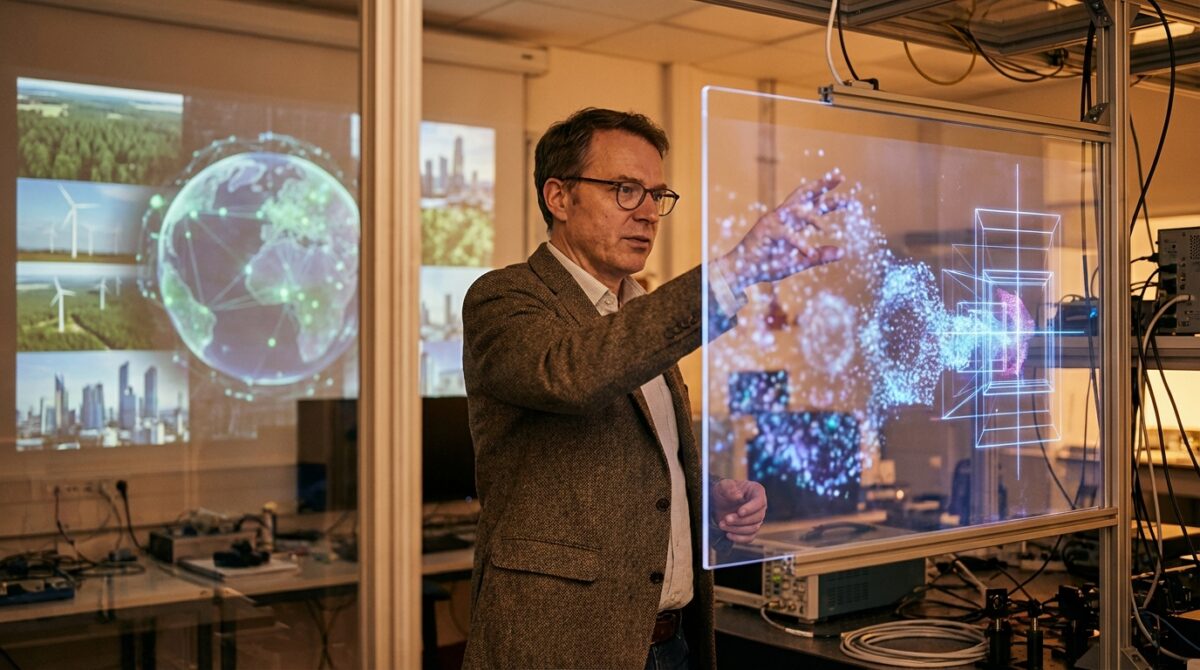

Building on the idea of “quantum Darwinism”, a team led by Steve Campbell at University College Dublin has reframed this tension as a question about understanding how information spreads. Their work studies how different observers, each accessing only fragments of the environment, still manage to agree on the same external facts, forming an objective, shared reality instead of private, incompatible worlds.

Remote Entangled Atoms Unite as a Single Sensor to Achieve Remarkable Precision

Ancient Humans Craft Oldest Known Wooden Tool in Stick Form

From quantum Darwinism to everyday consensus

Quantum Darwinism, first outlined by Wojciech Zurek in 2000 at Los Alamos National Laboratory, proposes that certain quantum states are “fitter” than others. These states imprint multiple copies of their information into the surrounding environment, much like successful genes spread through a population, creating the building blocks of objectivity.

Campbell’s group pushes this further. Instead of assuming perfect observers with flawless devices, they ask how agreement can still arise when measurements are noisy or limited. This mirrors real laboratories and even human cognition, where attention, prior beliefs and instruments rarely operate at theoretical perfection.

Why this quantum discovery matters for our shared reality

The research turns the emergence of objectivity into a problem in quantum sensing. Imagine observers trying to learn the frequency of light emitted by a source. In principle, a perfectly tuned quantum sensor could reach the best possible accuracy, captured mathematically by something called quantum Fisher information (QFI).

The team compared this ideal benchmark with more “ordinary” and even crude measurement schemes. Their calculations show that once the environmental fragments are large enough, these simpler measurements still converge toward the same accurate description of reality as the QFI limit. A basic detector can, over time, extract the same key facts as an exquisitely engineered device.

When imperfect measurements still create a common world

This finding has a disarming implication: objectivity does not require perfect observation. Many different, imperfect ways of probing the environment can still support a robust, shared reality. Observers who never coordinate their methods can nonetheless agree about the color of a cup or the trajectory of a satellite.

This resonates with social science research on how people construct common ground. Work such as shared reality and inner states about the world and the close-relationship framework in epistemic companions shows how interpersonal agreement emerges despite noisy communication. Physics now offers a parallel: many weak signals can still crystallize into consensus.

Technical details: quantum Fisher information and objectivity

QFI is a quantity from quantum metrology that tells you how much information about a parameter, such as a light frequency or magnetic field, is encoded in a quantum state. The higher the QFI, the more precisely that parameter can be estimated, in principle, with an optimally chosen measurement.

Campbell’s team uses QFI as a gold standard, then asks how far below this optimum real observers can fall while still converging on the same facts. Co-author Gabriel Landi, now at the University of Rochester, stresses that even relatively “silly” measurements succeed, provided they collect information from enough independent environmental copies.

From toy models to experimental quantum devices

The current models are deliberately simple, but they are designed to connect with realistic platforms. Quantum devices using trapped ions, superconducting qubits or light-based architectures already exploit QFI to push sensing to unprecedented limits, for instance in studies like minute spin shifts in quantum systems or magnetic activity linked to solar dynamics.

Applying this novel approach to such systems could allow researchers to measure, in the lab, how quickly objectivity “switches on”. By varying the size of the environmental fragments that qubits interact with, experimentalists can track when different detectors, or even different algorithms, start to agree on the same underlying physical quantities.

From physics to philosophy, cognition and collaboration

The implications reach beyond hardware. Philosophers and cognitive scientists, including Yuval Noah Harari in his recent work on objective, subjective and intersubjective layers of reality, have explored how societies converge on shared meanings. The trispectivism perspective on Harari’s framework aligns intriguingly with quantum Darwinism’s tiers of description.

Psychological research on sharing inner states and merging minds, and the synthesis in From Sharing-Is-Believing to Merging Minds, underscores how alignment about “what is real” underpins social connection. The physics result supplies a structural analogue: many partial, noisy glimpses can still sustain a coherent picture that guides collaboration.

Why Earth science and daily life benefit

Reliable objectivity matters wherever sensors inform decisions. Networks of satellites tracking auroral storms, such as those captured in space-based aurora observations, must combine multiple imperfect measurements into a single, trusted picture of near-Earth space. The same principle guides environmental arrays monitoring how mountain regions are heating rapidly.

On smaller scales, neurocognitive studies on why some minds stay sharp throughout life examine how brains integrate noisy signals into stable beliefs. Insights from quantum objectivity may help model how consciousness and knowledge stabilize across time, even as sensory inputs fluctuate and internal states drift.

Key ideas reshaping our understanding of shared reality

To keep the core contributions in view, it helps to group them as a compact set of insights. Each point shows how physics, psychology and philosophy are quietly converging on similar patterns.

- Objective reality can emerge from many imperfect measurements, not only idealised, optimal ones.

- Quantum Fisher information provides a benchmark for how fast and how precisely objectivity appears.

- Large environmental fragments act as information “amplifiers”, spreading facts to many observers at once.

- Social science work on being on the same wavelength mirrors this amplification in human communication.

- Interdisciplinary dialogue, from social cognition to climate sensing, stands to gain from this shared mathematical language.

Together, these strands trace a new route toward a more integrated understanding of how a single world appears to many different minds and instruments.

How does this research change our view of objective reality?

The work suggests that objective reality does not require perfect observers or flawless instruments. Instead, once enough environmental information is available, many different and even crude measurements can still lead observers to the same conclusions. Objectivity becomes a collective property of systems and their environments, rather than a feature that depends on a single, idealised measurement.

What is quantum Fisher information in simple terms?

Quantum Fisher information (QFI) is a way of quantifying how much information about a physical parameter is stored in a quantum state. The higher the QFI, the more accurately that parameter can be estimated with the best possible measurement. In this research, QFI acts as a reference standard to compare real, imperfect measurement strategies and see when they still support agreement on observable facts.

Does this have any impact on everyday technologies?

Yes. The same mathematics underpins quantum sensors, navigation systems, environmental monitoring networks and even medical imaging. Knowing that multiple imperfect detectors can still converge on reliable readings informs how engineers design distributed sensor arrays for climate observation, space weather forecasting or brain research, often with tight budget and energy constraints.

How is this related to psychological shared reality research?

How Obesity and High Blood Pressure Could Directly Trigger Dementia

How Menstrual Pads Could Unlock Women’s Secrets to Tracking Fertility Changes

Psychological studies, such as those summarised on PubMed and in works like Shared Reality: Experiencing Commonality with others’ Inner States, show how people construct a sense of common understanding about the world. The physics result offers a structural parallel: just as many incomplete conversations can still yield social consensus, many partial physical measurements can yield agreement about external properties.

Can these ideas help bridge science and philosophy of consciousness?

They contribute a useful framework. By showing how stable, observer-independent facts emerge from fundamentally probabilistic processes, the work gives philosophers and cognitive scientists a model for how coherent experiences arise from underlying neural and physical activity. It does not solve consciousness, but it clarifies how perceptions can be shared and coordinated across individuals and instruments.