Show summary Hide summary

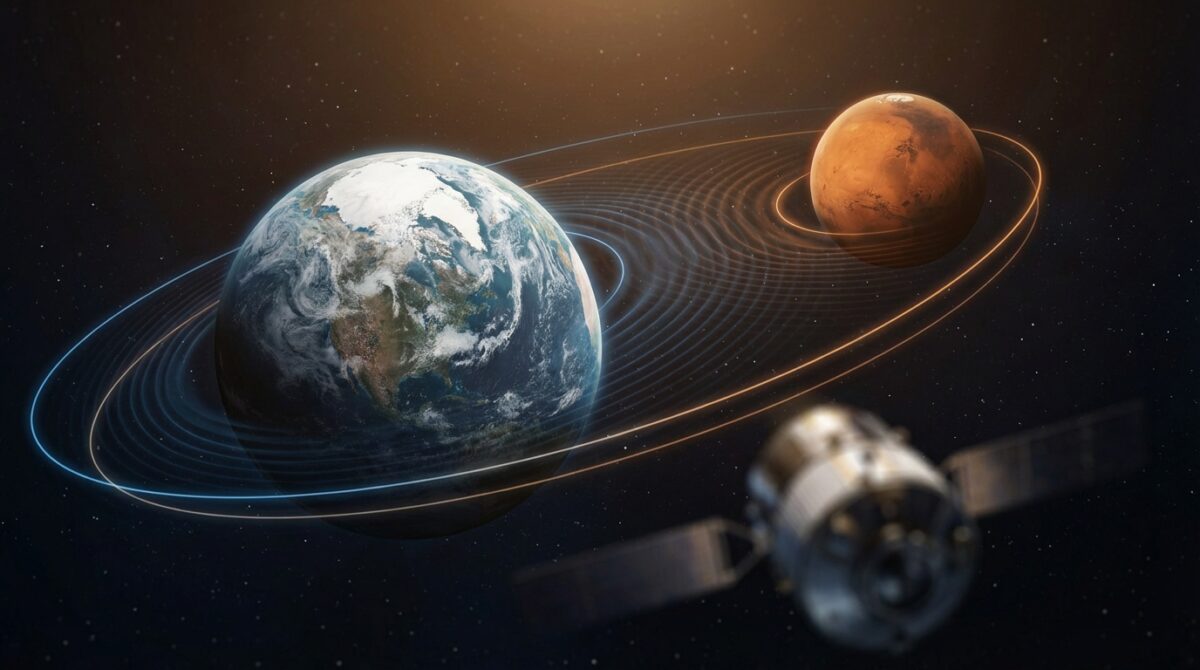

Every few million years, Earth slips in and out of deep freezes. New research suggests that a distant neighbour – Mars – is quietly helping to set that rhythm, reshaping how you think about our planet’s ice ages and long-term climate.

The idea sounds almost mythical: a smaller world, millions of kilometres away, nudging the timing of glaciers on Earth. Yet detailed computer models and ancient sediment records now indicate that this subtle planetary interaction leaves a measurable fingerprint in our planet’s history, and may change how scientists judge the stability of climates on distant exoplanets.

How Mars’ gravity links to Earth’s ice-age timing

Researchers led by Stephen Kane at the University of California, Riverside, used high-precision simulations of the solar system to test how Mars’ gravity reshapes Earth’s orbit. They virtually “turned the Red Planet’s mass knob” from zero up to 100 times its real value and watched how Earth’s orbital patterns evolved over millions of years.

Webb Captures the Last Radiant Exhalation of a Dying Star in the Helix Nebula

A Guide to Observing the Lunar X and V Phenomena

The team focused on long rhythms known as Milankovitch cycles, which describe slow shifts in Earth’s eccentricity (how stretched its orbit is) and axial tilt. These cycles control how sunlight is distributed across the globe, and therefore influence the onset and retreat of major glaciations. As reporting from recent coverage on tiny Mars’ big impact explains, Kane started out sceptical that a planet only one-tenth Earth’s mass could matter so much.

The 2.4‑million‑year “grand cycle” shaped by Mars

One key result centred on a roughly 2.4‑million‑year grand cycle in Earth’s orbital eccentricity. In the real solar system, Earth’s orbit slowly elongates and then rounds off again over this timescale, subtly altering how much solar energy different latitudes receive and pacing long-term climate transitions.

When the researchers removed Mars from the simulations, that 2.4‑million‑year pattern vanished, along with a familiar ~100,000‑year cycle associated with eccentricity changes. Coverage from Earth.com on Mars helping set ice-age timing highlights that without Mars, the “landscape” of how often severe glacial phases occur would look very different, even though ice ages would still happen for other reasons.

Milankovitch cycles, axial tilt and seasonal rhythm

To understand why these results matter, it helps to revisit what Milankovitch cycles actually do. Over tens to hundreds of thousands of years, Earth’s axial tilt and orbital shape drift. That drift changes the contrast between seasons and the distribution of sunlight across hemispheres, which in turn affects how ice sheets grow or retreat.

Mars gently modulates two of these key properties: Earth’s eccentricity and its tilt. The study showed that when Mars’ simulated mass increased, the eccentricity cycles became shorter and more intense. A longer, ~405,000‑year eccentricity rhythm, driven mainly by Venus and Jupiter, remained steady, confirming that Mars is influential but not dominant in the grand pattern of orbital change described by resources such as EarthSky’s overview of Mars and Earth’s ice ages.

Mars as a subtle stabiliser of Earth’s axial tilt

Beyond orbit shape, the simulations explored how Mars affects Earth’s axial tilt, which normally oscillates over about 41,000 years. That tilt determines how strong seasons are. Slight changes can decide whether summers are warm enough to melt winter snows at high latitudes or allow ice sheets to thicken.

Interestingly, Mars appears to have a gentle stabilising role. When the Red Planet’s mass was increased in the models, the tilt cycle occurred less frequently; when Mars was shrunk, the wobble sped up. Reports such as analyses on how Mars’ gravity may help control ice-age cycles describe this as Mars “punching above its weight,” quietly shaping the seasonal rhythm that feeds into long-term climate patterns.

From simulations to ancient rocks and future climate insight

The orbital patterns Kane’s team modelled do not remain abstract equations. They leave signatures in sediments and fossils that geologists read like a deep-time calendar. Rhythmic layers of limestone, dust and marine microfossils often line up with predicted Milankovitch cycles, including the 2.4‑million‑year beat now linked strongly to Mars.

Articles such as UCR’s report on Mars’ quiet impact on climate and analyses of the long-term climate story emphasise that the new simulations match patterns already hinted at in rock cores. Those matches build confidence that the Red Planet’s gravitational tug is part of the explanation for why ice ages follow a particular tempo rather than arriving randomly.

Why Mars and orbital architecture matter for exoplanets

This research stretches far beyond curiosity about our own glacial history. Space agencies such as NASA and the European Space Agency (ESA) are investing billions of dollars in missions that hunt for Earth-like worlds. To judge whether those planets can host stable climates, scientists must understand not only the star they orbit, but the full orbital architecture of each system.

Sean Raymond at the University of Bordeaux argues that smaller planets similar to Mars may strongly influence climate stability on those distant worlds. As highlighted by resources like ZME Science’s summary of Mars-triggered ice ages and the explanatory guide on how Mars might control Earth’s ice ages, ignoring low-mass neighbours could lead to misleading assessments of an exoplanet’s long-term habitability.

What this means for life on Earth and future research

The study does not claim that Mars directly warms or cools Earth in the way greenhouse gases do. Instead, it highlights how gravitational nudges far from our atmosphere set the tempo on which the climate system plays. Over hundreds of thousands of years, those orbital changes steer when ice sheets advance or retreat, reshaping coastlines and ecosystems.

For climate modelers, this work offers a reminder: understanding future change requires a firm grasp of the slow background rhythms as well as rapid human-driven warming. For planetary scientists planning the next generation of telescopes and missions, from advanced ESA observatories to NASA’s future flagship exoplanet surveyors, the message is clear. To understand a world’s climate, you must map every meaningful planetary interaction, however small it seems.

Key takeaways for readers and researchers

To make sense of this complex story, it helps to keep a few core ideas in mind. These points connect the distant pull of Mars to questions that matter on Earth and in exoplanet science.

- Mars subtly shapes Earth’s orbit: Its gravity helps maintain a 2.4‑million‑year eccentricity cycle and influences ~100,000‑year patterns linked to ice-age pacing.

- Axial tilt and seasons respond: Small changes in Earth’s tilt cycle alter seasonal contrasts, feeding into glacier growth and retreat.

- Milankovitch cycles remain central: Mars modifies, rather than replaces, the classic orbital cycles that govern long-term climate evolution.

- Exoplanet climates need context: Assessing habitability requires knowledge of every significant planet in a system, not just the “Earth twin.”

- Climate history informs climate future: Understanding ancient orbital rhythms provides a baseline against which modern, rapid warming can be measured.

Does Mars control Earth’s climate?

Mars does not directly control Earth’s climate or daily weather. Instead, its gravity slightly alters Earth’s long-term orbit and axial tilt cycles. Those slow changes influence how sunlight is distributed over tens of thousands to millions of years, which in turn affects the timing and intensity of ice ages. Human-driven greenhouse gas emissions dominate current climate change on human timescales.

What is the 2.4‑million‑year grand cycle linked to Mars?

The 2.4‑million‑year grand cycle is a long-term change in Earth’s orbital eccentricity, the degree to which its orbit is stretched. Simulations show that Mars’ gravity helps maintain this rhythm. When Mars is removed from models, the cycle disappears, suggesting the Red Planet plays a key role in pacing some of Earth’s deep-time climate variations.

How do Milankovitch cycles trigger ice ages?

Milankovitch cycles describe predictable changes in Earth’s orbit, axial tilt and the direction of its axis. These shifts modify how much solar energy reaches different latitudes and seasons. When conditions favour cooler summers at high latitudes, ice sheets can grow and persist, leading to ice ages. Warmer summers promote melting and interglacial periods.

Why does Mars matter for exoplanet habitability?

How SpaceX’s Starlink Successfully Avoided 300,000 Satellite Collisions in 2025

Astronomers Unveil a Breathtaking Radio Color Portrait of the Milky Way

The Mars–Earth example shows that even relatively small planets can strongly influence another world’s orbital stability and long-term climate. For exoplanets, this means researchers must consider the full planetary system, including low-mass neighbours, when evaluating whether a planet can sustain a stable, life-supporting climate over geological timescales.

Can changing Mars’ mass in reality alter Earth’s climate?

The scenarios where Mars becomes heavier or lighter exist only inside computer simulations. They help scientists understand how sensitive Earth’s orbital cycles are to different gravitational setups. Mars’ actual mass is fixed, so these hypothetical cases do not represent real future changes, but they provide insight into planetary dynamics across the universe.