Show summary Hide summary

- What we now know about fluffy infant planets

- How astronomers weighed planets around a noisy young star

- Inside the early stage: puffy atmospheres and shrinking worlds

- V1298 Tau as a laboratory for planetary formation

- What this tells us about protoplanetary disks and our own system

- Key insights to remember

- What makes these planets ‘fluffy’ compared with others?

- How does this study change theories of planetary formation?

- Can we say these fluffy infant planets will definitely become super-Earths?

- Why is the Doppler method not used for V1298 Tau?

- What are the next steps for studying this hidden phase?

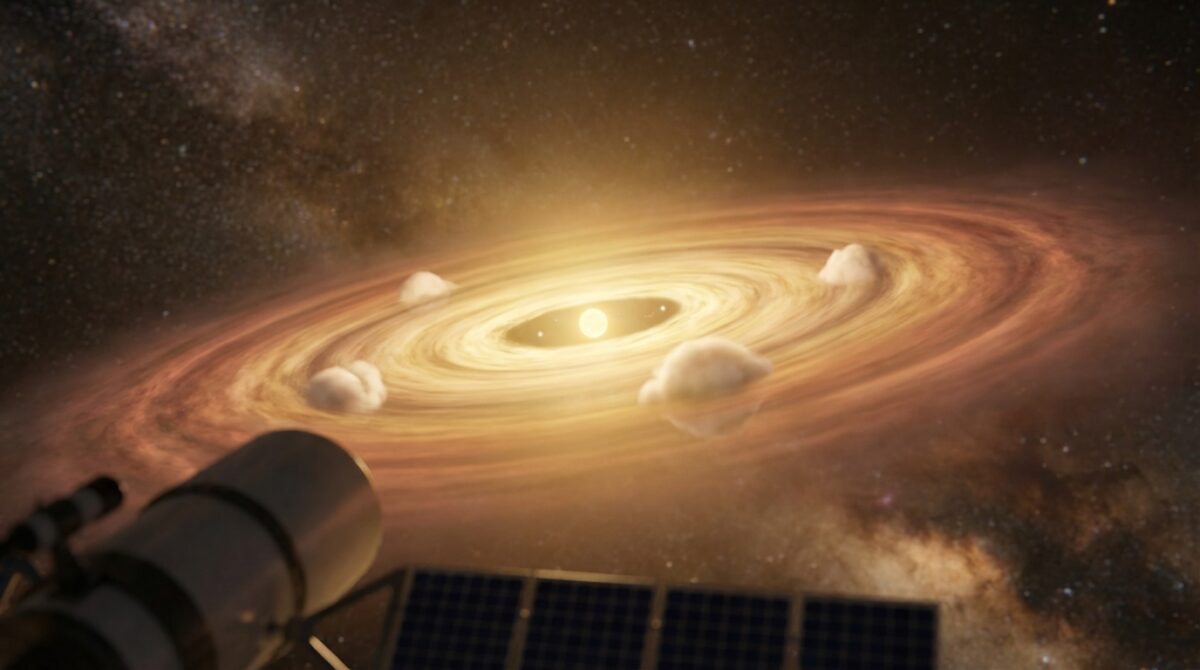

What if the most common worlds in our galaxy begin life not as compact rocks or neat mini-Neptunes, but as fluffy infant planets as light as cotton candy? That is what a new study of the young star V1298 Tau now strongly suggests, uncovering a hidden phase in planetary formation that astronomers had only guessed existed.

This work, led by John Livingston at the Astrobiology Center in Tokyo with colleagues from UCLA, Imperial College London and the Flatiron Institute, delivers a rare “before and after” snapshot. By weighing four very young planets in one system, the team shows how gas-rich giants can rapidly shrink into the super-Earths and sub-Neptunes that dominate the Milky Way.

What we now know about fluffy infant planets

At the heart of the discovery sits V1298 Tau, a star only about 20 million years old. Compared with the Sun’s 4.5 billion years, that age makes it a true adolescent. Orbiting this star, four planets with sizes between Neptune and Jupiter appear dramatically bloated, yet surprisingly lightweight.

Robotic Explorers Venture into Lunar Lava Tubes, Paving the Way for Future Moon Bases

Radio Waves Unveil the Secrets Leading Up to a Star’s Cataclysmic Explosion

The team finds that these worlds are only about 5 to 15 times Earth’s mass, despite being up to ten times Earth’s radius. That combination translates to extremely low density, confirming that young planets can pass through a brief, “puffy” stage before they evolve into the compact super-Earths and sub-Neptunes already catalogued by missions like Kepler and TESS.

A hidden phase in planetary formation finally measured

For more than a decade, surveys have shown that most Sun-like stars host at least one planet between Earth and Neptune in size, orbiting closer than Mercury. Our own Solar System lacks these worlds, which raised a simple question: how do such planets form, and why are they so common elsewhere?

This new study argues that many of them probably start life as low-density giants, swaddled in thick envelopes of hydrogen and helium. Over hundreds of millions of years, intense starlight and shrinking interiors strip away part of that gas. The result is a compact planet, smaller but still richer in volatiles than Earth. V1298 Tau offers a live demonstration of this early stage of planet evolution.

How astronomers weighed planets around a noisy young star

Measuring the mass of planets around a star like V1298 Tau is notoriously tricky. Young stars are magnetically active, covered with starspots and flares that distort the usual Doppler measurements astronomers use to detect the tiny wobble caused by orbiting planets. For this system, that standard technique was essentially unusable.

Instead, the research team relied on a method that has become a powerful plan B in crowded systems: Transit-Timing Variations (TTVs). Over roughly ten years, they tracked each time the planets passed in front of the star, causing a small dip in brightness. Careful timing of those dips revealed subtle delays and advances caused by the planets tugging on each other.

Transit-Timing Variations: planets weighing their neighbours

In a perfectly clockwork system, every transit would occur at fixed intervals. V1298 Tau did not behave that way. Each planet’s transit shifted by minutes, the sign of neighboring worlds exchanging gravitational nudges. By modeling those shifts, the researchers turned the system into its own weighing machine.

From these TTVs, they derived individual planetary masses with enough precision to rule out denser, rocky compositions. Confidence levels vary from planet to planet, but collectively they support a picture of very low densities and thick envelopes — a strong quantitative test of long-standing theories on accretion and atmospheric loss in young systems.

Inside the early stage: puffy atmospheres and shrinking worlds

To understand what these numbers mean physically, the team combined the mass and radius estimates with models of planet evolution. If the planets had simply formed and cooled slowly, theory predicts they would be much more compact by now. Instead, they appear oversized for their age, implying a violent early history.

According to the models developed at Imperial College London, the planets around V1298 Tau must have already lost huge fractions of their primordial atmospheres. As the protoplanetary disks of gas and cosmic dust surrounding the star dispersed, the planets suddenly found themselves exposed to harsher stellar radiation, which scoured away part of their hydrogen-helium envelopes.

From cotton candy giants to super-Earths and sub-Neptunes

The current snapshot suggests these infant planets are midway through a dramatic slimming process. Over the next few billion years, continued atmospheric escape and internal cooling will likely shrink them further. The end products should resemble the close-in super-Earths and sub-Neptunes now considered the galaxy’s “default” planets.

Astronomers sometimes compare V1298 Tau to a fossil like “Lucy” in human evolution — not because it is unique, but because it sits at a transitional stage. It bridges the gap between very young systems where planets are just emerging from disks and mature planetary architectures recorded by thousands of exoplanet surveys.

V1298 Tau as a laboratory for planetary formation

To make sense of this new phase, it helps to picture a training-camp scenario. Imagine a coach, Mara, running simulations of young planetary systems for a university team preparing for an exoplanet data challenge. V1298 Tau becomes her textbook example: a star that still carries the hyperactivity of youth, surrounded by planets that have not yet settled into their final shapes.

Mara shows her students how the system captures multiple key ingredients in one place: leftover gas from the birth cloud, evolving orbits, and planets transitioning from gas-rich giants to compact worlds. Each measurement — timing, mass, radius — becomes a clue to how planetary formation unfolds once accretion from the original disk slows down.

What this tells us about protoplanetary disks and our own system

Compared with images of protoplanetary disks packed with rings and gaps, such as those described in recent high-resolution disk studies, V1298 Tau captures a slightly later snapshot. The bulk of the disk is gone, but the planets still carry its imprint in their low-density envelopes.

For our Solar System, the results raise an intriguing possibility. Perhaps Jupiter and Saturn also experienced an early, puffier phase, while inner rocky planets like Earth formed in regions where gas disappeared faster. This study does not prove that scenario, but it sharpens the questions researchers now ask about why our planetary line-up differs from the galactic average.

Key insights to remember

- Most Sun-like stars host at least one planet between Earth and Neptune in size, often closer in than Mercury.

- V1298 Tau’s four planets are unusually large yet low-mass, confirming a transient “fluffy” phase.

- Transit-Timing Variations offered a way to weigh planets around a very active young star.

- Rapid atmospheric loss and cooling likely drive the transition to compact super-Earths and sub-Neptunes.

- Our Solar System might have followed a different pathway, explaining the absence of close-in mini-Neptunes.

What makes these planets ‘fluffy’ compared with others?

Their radii are five to ten times Earth’s, but their masses are only five to fifteen times higher. This combination means their average density is extremely low, indicating very extended hydrogen-helium atmospheres that have not yet fully contracted or evaporated.

How does this study change theories of planetary formation?

It provides direct evidence for a short-lived phase where young, Neptune-to-Jupiter-sized planets are bloated and lightweight. Models must now account for rapid early atmospheric loss and contraction, instead of assuming a slow, steady cooling into the planets we observe today.

Can we say these fluffy infant planets will definitely become super-Earths?

The data strongly suggest they will shrink into more compact worlds, probably in the super-Earth or sub-Neptune category, but there is some uncertainty. Long-term evolution depends on factors such as stellar activity, initial composition and how much atmosphere they continue to lose.

Why is the Doppler method not used for V1298 Tau?

A Sudden Signal Flare Unmasks the Elusive Companion Behind Fast Radio Bursts

Dark Stars: Unveiling Three Key Mysteries of the Early Universe

The star is very young and magnetically active, with starspots and flares that create noisy signals in its spectrum. That variability overwhelms the tiny Doppler wobble caused by the planets, so transit-timing variations offer a cleaner path to estimating their masses.

What are the next steps for studying this hidden phase?

Future work will combine long-term transit monitoring, improved atmosphere models and direct imaging of similar systems. As instruments become more sensitive, astronomers expect to probe the composition of these puffy atmospheres and test how universal this early evolutionary stage really is.