Show summary Hide summary

- Long COVID brain fog: what the study uncovered

- Detailed results: income and culture, not the virus

- Shared neurological symptoms behind the numbers

- How to interpret causality, limitations, and next steps

- Real-world implications for patients and policy

- Why does long COVID brain fog seem worse in the United States?

- Does higher reporting mean brain fog is less common in countries like India or Nigeria?

- What neurological symptoms are most often linked to long COVID?

- Can brain fog from long COVID be treated or reversed?

- What should someone do if they suspect post-COVID cognitive problems?

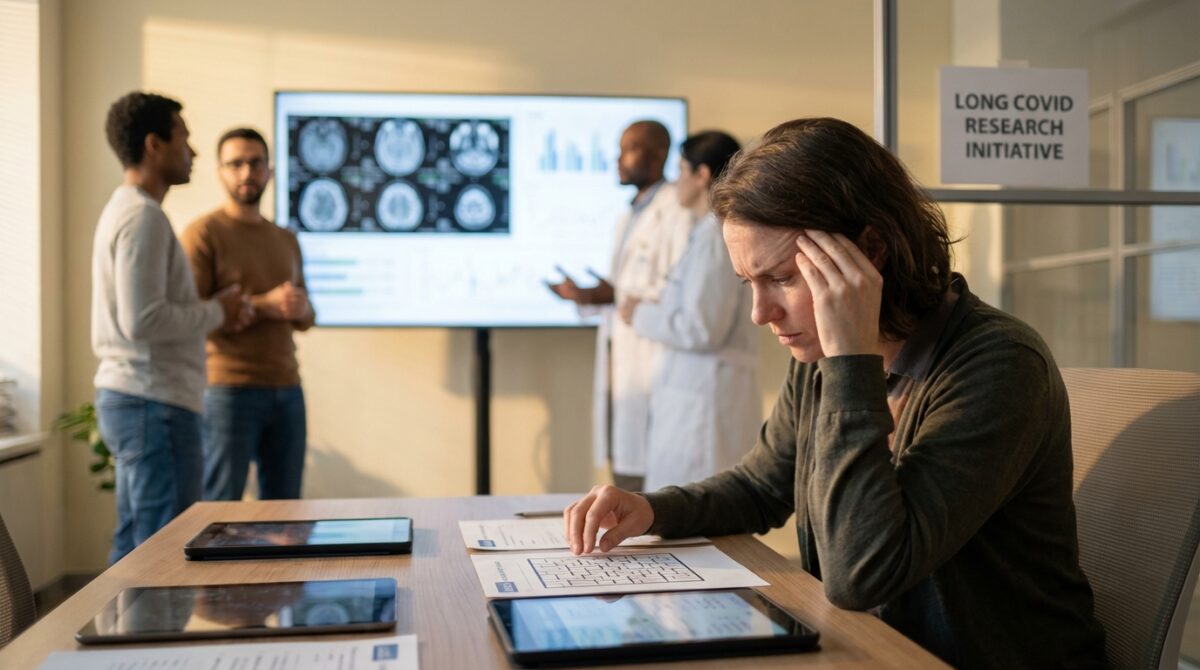

What we now know about Long COVID is unsettling: in one of the largest global comparisons to date, adults in the United States report far more Cognitive Fog, depression, and sleep problems than patients with similar infections in India, Nigeria, or Colombia. The virus is the same; what changes is society.

The research, led by neurologist Dr. Igor Koralnik at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and published in Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, tracked over 3,100 people living with Long COVID between 2020 and 2025. It suggests that how debilitating Brain Fog feels is shaped less by biology and more by culture, health systems, and what care is even available.

Long COVID brain fog: what the study uncovered

The central finding is stark. Among non-hospitalized patients, 86% of U.S. participants reported Brain Fog, compared with 63% in Nigeria, 62% in Colombia, and only 15% in India. These patients all had confirmed COVID infections and persistent Neurological Symptoms consistent with Post-COVID Syndrome.

Scientists Transform Tumor Immune Cells into Potent Cancer-Fighting Warriors

Exploring How Genetics and Environment Each Shape Half of Our Lifespan

Psychological symptoms followed a similar gradient. About three in four U.S. patients reported depression or anxiety, compared with roughly 40% in Colombia and under 20% in Nigeria and India. Sleep problems were also more frequent in America: nearly 60% reported insomnia, while only around a third or fewer did so at the other sites.

How researchers compared brain fog across continents

The team designed a straightforward but powerful method: adults with ongoing neurological complaints after COVID were evaluated at four academic medical centers in Chicago (U.S.), Medellín (Colombia), Lagos (Nigeria), and Jaipur (India). Most had never been hospitalized for their initial infection, making extreme intensive care complications an unlikely explanation.

Clinicians at each site used standardized neurological, cognitive, and quality-of-life assessments adapted from existing tools. This allowed cross-site comparison while respecting local language and context. The study was observational, meaning researchers tracked symptoms rather than assigning treatments, so the findings show patterns and associations rather than strict cause-and-effect.

Detailed results: income and culture, not the virus

When statisticians analyzed the data, symptom patterns clustered more by national income level than by geography. The U.S. and Colombia, both higher-income or upper-middle-income settings in this sample, showed similar profiles: higher reporting of Cognitive Fog, mood symptoms, and sleep disruption. Nigeria and India, classified as lower-middle-income, formed a second cluster with substantially lower reported burdens.

This pattern points away from viral mutations and toward social context. According to Koralnik and colleagues, the differences are unlikely to mean that people in India or Nigeria are magically spared Chronic Fatigue or Brain Fog. Instead, they likely reflect what is talked about, what is stigmatized, and what is worth seeking help for in each healthcare system.

Cultural silence and limited care for mental health

In the U.S. and Colombia, discussing Mental Health and cognition has become more accepted, at least in clinical settings. Patients like “Maria,” a 38‑year‑old office worker in Chicago, feel able to say, “My thoughts feel slow, I lose words, I cannot manage spreadsheets anymore.” That language opens the door to detailed reporting of Neurological Symptoms.

In contrast, Koralnik notes that in Nigeria and India, many patients face a mix of stigma, religious interpretations, and low health literacy around mood and cognitive problems. If sadness is seen as weakness, or confusion as a spiritual issue, people may either under-report symptoms or frame them only as physical fatigue. A lack of neurologists, psychiatrists, and structured clinics for Post-COVID Syndrome further dampens reporting.

Shared neurological symptoms behind the numbers

Despite the differences in reported intensity, certain complaints were common across all four countries. The most frequent included Brain Fog, persistent fatigue, myalgia (muscle pain), headache, dizziness, and sensory changes such as numbness or tingling. These align with independent reviews of Long COVID neurology, such as analyses summarized by recent brain fog overviews.

Several teams worldwide, including work cited in neuro-COVID research digests, have linked these symptoms with altered brain connectivity, immune activation, and disrupted stress responses. The Northwestern-led study did not directly scan every participant’s brain, so it cannot assign a biological mechanism to each symptom. Still, it aligns with evidence that Long COVID disrupts brain adaptability and emotional balance.

Work, identity, and the healthcare impact

The consequences go far beyond discomfort. The study’s authors emphasize that these neurological and psychological issues strike young and middle-aged adults, often in full-time employment. Many American participants reported that Cognitive Fog and Chronic Fatigue interfered with tasks that once felt routine: managing email, driving, budgeting, or supervising teams.

For health systems already strained, this translates into a mounting Healthcare Impact. Patients require serial visits, neuropsychological testing, occupational therapy, and sometimes long-term disability support. Yet even in the U.S., trials of candidate treatments have been mixed; for example, some promising Brain Fog therapies have failed to show clear benefit in randomized studies, reminding clinicians how much remains uncertain.

How to interpret causality, limitations, and next steps

The authors are careful about what their data can and cannot prove. The study does not show that living in the U.S. directly causes more severe Long COVID, nor that Americans are “sicker” than patients elsewhere. It shows that U.S. patients report a heavier burden of cognitive and emotional symptoms when systematically asked in specialist clinics.

Several limitations temper the results. The sample comprises people who reached academic centers, which likely over-represents individuals with access to care and time to seek it. Symptom assessment tools, while standardized, were not identical across countries, and cultural nuances in language may influence how concepts like “Brain Fog” or “depression” are understood.

Real-world implications for patients and policy

Even with those caveats, the findings carry practical implications. Health authorities in high-income settings may need to scale up cognitive rehabilitation, workplace accommodations, and mental health integration for Long COVID clinics. Northwestern’s group is already testing the same rehabilitation protocol used at Shirley Ryan AbilityLab in Chicago in Colombia and Nigeria to see whether structured strategies can relieve Brain Fog across cultures.

For readers living with lingering Post-COVID Syndrome, the message is twofold. First, their experience of Cognitive Fog, sadness, or anxiety is widely shared and biologically plausible. Second, symptom intensity may be shaped partly by stress, expectations, and support systems, so addressing social and psychological context can be as important as targeting viral remnants or inflammation.

- Seek multidisciplinary care: combine neurology, mental health, and rehabilitation rather than relying on one specialty alone.

- Track symptoms: simple diaries of sleep, exertion, and cognition help clinicians see patterns and avoid overexertion crashes.

- Ask about trials: many centers are testing cognitive training, medications, or pacing protocols for Long COVID.

- Protect work capacity: negotiate flexible hours or remote days while symptoms fluctuate.

- Address stigma: share validated resources with family or employers to frame Brain Fog as a genuine post-viral issue.

Resources from academic centers, such as practical guides on managing long COVID brain fog, can help patients and clinicians translate this growing science into daily strategies, even as researchers refine the underlying biology.

Why does long COVID brain fog seem worse in the United States?

The international study led by Northwestern University suggests that U.S. patients report more Cognitive Fog and mental health symptoms partly because it is more acceptable to discuss these problems and because access to neurological and psychiatric care is higher. This does not prove Americans have more severe disease, but rather that their symptoms are more often recognized, named, and medically documented.

Does higher reporting mean brain fog is less common in countries like India or Nigeria?

Not necessarily. Lower reported rates in India and Nigeria may reflect stigma around Mental Health, fewer specialists, and different beliefs about cognitive complaints. Some people may express the same distress mainly as fatigue or physical weakness, or may not seek care at all, so the true burden of Post-COVID Syndrome could be under-estimated.

What neurological symptoms are most often linked to long COVID?

Across all sites in the study, patients frequently described Brain Fog, trouble with attention and memory, Chronic Fatigue, headaches, dizziness, muscle pain, and tingling or numbness. Many also reported insomnia and low mood. Other research, including neuroimaging work, indicates that long COVID can alter brain networks involved in attention, sensory processing, and emotional regulation.

Can brain fog from long COVID be treated or reversed?

How AI-Powered Mammograms Are Reducing the Risk of Aggressive Breast Cancer

This Doctor is Searching for Top-Quality Gut Health Through Exceptional Stool Samples

There is no single proven cure, but several approaches show promise. Structured cognitive rehabilitation, energy management or pacing, treatment of sleep and mood disorders, and gradual physical conditioning can all help some people. Ongoing clinical trials are testing medications and neurorehabilitation programs, though some therapies once considered promising have not yet shown clear benefit when rigorously studied.

What should someone do if they suspect post-COVID cognitive problems?

Anyone noticing persistent Cognitive Fog, memory issues, or concentration problems months after COVID should consult a clinician familiar with Long COVID. Bringing a symptom diary and work examples can clarify the pattern. A thorough evaluation can rule out other causes, guide referrals to neurology or rehabilitation, and help arrange workplace adaptations while recovery continues.