Show summary Hide summary

- Key finding: An internal exercise sensor inside bone marrow

- Methodology: From biomechanics to molecular switches

- Detailed results: Why aging bones lose the exercise advantage

- From exercise benefits to “exercise mimetics” for Bone Health

- Limitations, open questions and future research directions

- Does this discovery mean people can stop exercising for bone health?

- Who could benefit most from Piezo1-targeting therapies?

- How does this research change current osteoporosis treatment?

- Is there evidence that similar mechanisms exist in humans?

- When might an ‘exercise mimetic’ for bones become available?

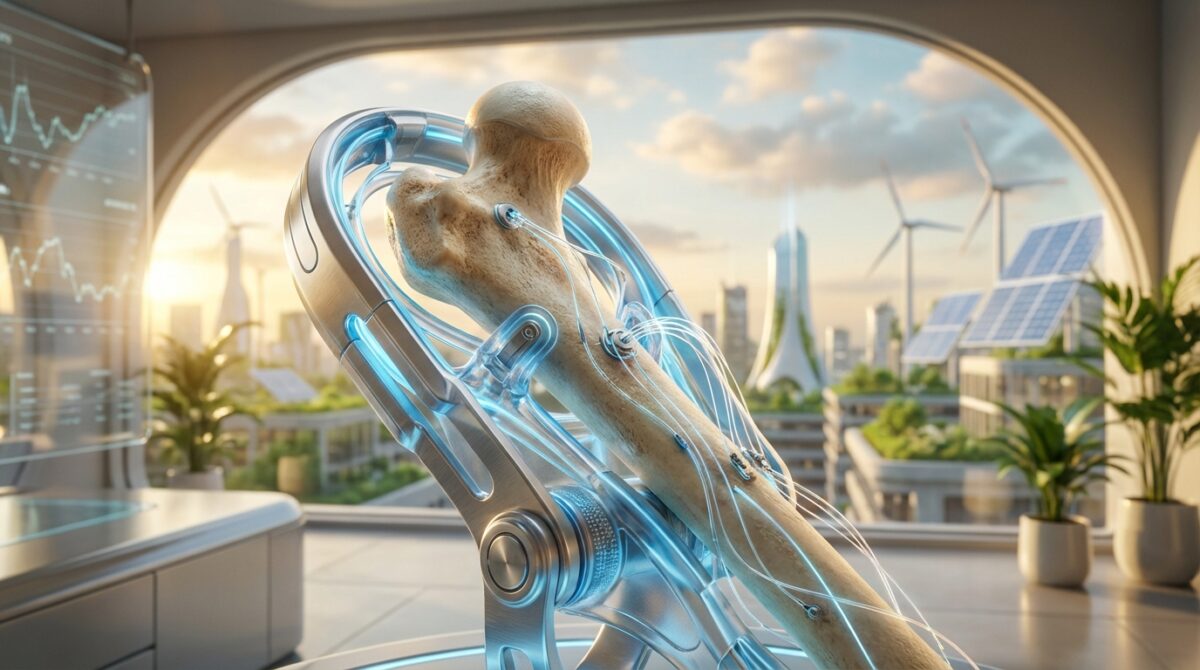

What if frail bones could receive exercise benefits without a single step being taken? A new study from the University of Hong Kong suggests that bones may one day be “trained” without physical movement, using a molecular switch hidden deep in the marrow.

This new discovery does not replace walking or strength training, but it explains how movement is translated into stronger bones at the cellular level. That knowledge could reshape Bone Health strategies for older adults, bedridden patients and people living with chronic disease.

Key finding: An internal exercise sensor inside bone marrow

Researchers at the LKS Faculty of Medicine, University of Hong Kong (HKUMed) have identified a protein called Piezo1 on bone marrow stem cells that acts as an internal “exercise sensor”. When activated by mechanical forces, Piezo1 encourages osteogenesis – the formation of new bone – and suppresses fat accumulation inside the skeleton.

Combating Measles Resurgence: The Crucial Battle Against the Spread of Misinformation

Scientists Uncover the Mystery Behind Earth’s Most Bizarre Fossils

The work, led by Professor Xu Aimin and Dr Baile Wang from HKUMed’s Department of Medicine, was published in the journal Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy. Using mouse models and human stem cells, the team showed that activating Piezo1 helps protect the musculoskeletal system even when bones are exposed to aging-related stress.

How the study was carried out and why it matters

In simple terms, the methodology followed one sentence: the team compared what happens to bones when Piezo1 works normally versus when this sensor is removed or blocked, in both animals and human cells. They then tracked changes in bone density, marrow fat, inflammation and cellular signaling pathways.

This approach allowed the scientists to distinguish correlation from mechanism. They did not only observe that active people have stronger bones, as reports like existing endocrinology reviews on exercise and bone health already describe. They identified a specific molecular gatekeeper that translates movement into biological change.

Methodology: From biomechanics to molecular switches

The project combined biomechanics, stem cell biology and pharmacology. In mouse experiments, researchers altered the Piezo1 gene in mesenchymal stem cells – the versatile cells in bone marrow that can become bone, fat or cartilage. Some mice had normal Piezo1, others had it partially or completely disabled.

Both groups were then exposed to different levels of mechanical loading, mimicking varied physical activity. Scientists measured bone density, structure and marrow composition, and analysed non-mechanical stimuli such as inflammatory molecules that can influence bone remodeling even when movement is limited.

Human cell experiments and signaling pathways

In parallel, human mesenchymal stem cells grown in vitro were subjected to controlled pressure and stretching, simulating the forces bones experience during walking or lifting. When Piezo1 was activated, cells preferentially turned into bone-forming osteoblasts. When Piezo1 was silenced, they shifted towards fat cells instead.

The team mapped key cellular signaling cascades triggered by Piezo1, including inflammatory mediators like Ccl2 and lipocalin‑2. Blocking these signals partly restored healthier bone formation, strengthening the case that Piezo1 sits at the top of a broader network that steers marrow fate.

Detailed results: Why aging bones lose the exercise advantage

The data help clarify why older adults experience faster bone loss. With age, mesenchymal stem cells increasingly become fat rather than bone, a trend that weakens the skeleton. In the HKUMed models, reduced Piezo1 activity accelerated this shift, even under normal loading conditions.

Mice lacking Piezo1 in their marrow stem cells showed lower bone mass, higher fracture risk and more inflammatory markers. Their marrow cavities filled with fat, crowding out bone tissue and undermining the structural integrity of the musculoskeletal system.

Numbers, risk and global context

The findings sit against a stark epidemiological background. According to the World Health Organization, roughly one in three women and one in five men over 50 will suffer an osteoporosis-related fracture. In Hong Kong alone, about 45% of women and 13% of men aged 65 and above live with osteoporosis.

Although the HKUMed work is preclinical and does not yet provide population-level statistics, it supports patterns already observed in large cohorts summarised by international reviews and resources such as recent analyses of exercise benefits for bones. The novelty lies in tracing those patterns back to a tangible molecule that can, in principle, be targeted.

From exercise benefits to “exercise mimetics” for Bone Health

The most provocative implication is the prospect of pharmacological “exercise mimetics” for Bone Health. By designing drugs that activate Piezo1 or its downstream pathways, researchers hope to imitate some of the protective effects of weight-bearing activity.

For someone like Mei, a hypothetical 82‑year‑old woman recovering from a hip fracture and unable to stand, such a therapy could slow further bone loss while she remains immobile. It would not replace rehabilitation, but it might prevent a second fracture that could end her independence.

Potential therapeutic applications and limits

Several therapeutic applications are being explored conceptually:

- Short‑term support for bedridden patients during hospital stays or lengthy recovery.

- Adjunct treatment for severe osteoporosis, combined with nutrition and carefully monitored physical activity.

- Targeted protection for people with chronic conditions that restrict movement, such as advanced heart failure or neurological disease.

However, any future “exercise-in-a-pill” will address only part of what movement does. Exercise also benefits immunity, metabolism and mental health, as highlighted by resources on immunity and bone-supporting activity. Piezo1‑based strategies would focus mainly on osteogenesis and marrow composition.

Limitations, open questions and future research directions

The HKUMed study remains at the level of animal models and cell cultures. No clinical trials have yet tested Piezo1‑targeting drugs in humans, and long‑term safety profiles are unknown. The sample sizes in laboratory experiments, while adequate for mechanistic research, do not provide population-level risk estimates or guarantees.

There is also the issue of causation versus context. Although manipulating Piezo1 clearly altered bone outcomes in controlled conditions, human Bone Health depends on nutrition, hormones, other non-mechanical stimuli and genetic background. Future research, including work like emerging skeletal stem cell studies from institutions such as Stanford, will need to integrate these dimensions into broader treatment strategies.

Does this discovery mean people can stop exercising for bone health?

No. The HKUMed research identifies Piezo1 as a key sensor that explains how movement protects bones, but it does not replace physical activity. Future drugs might mimic some exercise benefits for the skeleton, especially in people who cannot move, yet full-body exercise still supports muscles, heart, brain and immunity in ways a pill cannot copy.

Who could benefit most from Piezo1-targeting therapies?

The main candidates are older adults with osteoporosis, patients confined to bed after injury or surgery, and individuals with chronic illnesses that severely limit mobility. For these groups, activating the Piezo1 pathway could help preserve bone mass during periods when conventional weight-bearing exercise is impossible or unsafe.

How does this research change current osteoporosis treatment?

Current approaches rely on calcium, vitamin D, lifestyle changes and drugs that slow bone breakdown or stimulate formation. The Piezo1 discovery adds a potential new class of treatments that harness the biomechanics of movement at a molecular level. If confirmed in humans, such therapies would complement rather than replace existing medications and physiotherapy.

Is there evidence that similar mechanisms exist in humans?

A Century-Long Stonehenge Enigma Poised for Breakthrough Resolution

Discovering a Novel Approach to Understanding Our Shared Reality

Yes. The HKUMed team used both mouse models and human mesenchymal stem cells, and Piezo1 behaved consistently as a mechanosensor in both settings. However, researchers still need clinical trials to test whether activating this pathway in real patients safely produces meaningful improvements in bone density and fracture risk.

When might an ‘exercise mimetic’ for bones become available?

Drug development is a long process. After mechanistic studies, candidate molecules must pass toxicity tests, phased clinical trials and regulatory review. Even with intense interest, any Piezo1-based therapy for Bone Health is likely several years away, and timelines will depend on safety, efficacy and funding.