Show summary Hide summary

- Dark Oxygen mystery in a deep-sea mining hotspot

- How researchers will test the dark oxygen hypothesis

- Inside the deep-sea landers and lab simulations

- Scientific controversy, mining pressures and environmental impact

- Why dark oxygen matters for Earth and future exploration

- What you can watch for in the coming years

- What exactly is dark oxygen in the deep sea?

- How are researchers testing whether nodules produce oxygen?

- Why does dark oxygen matter for deep-sea mining plans?

- Could the dark oxygen findings be an experimental error?

- What is the connection between dark oxygen and astrobiology?

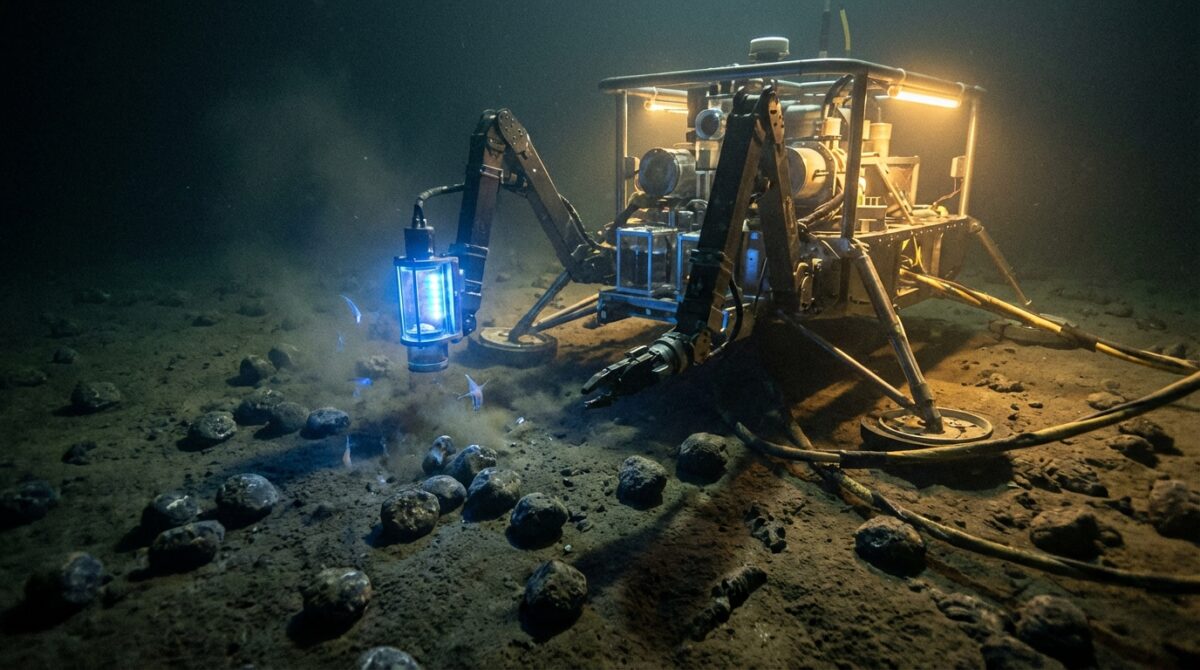

At the bottom of the Pacific, in darkness deeper than any subway tunnel or mine, rocks that look like potatoes appear to be exhaling oxygen. This disputed phenomenon, called Dark Oxygen, is pulling deep-sea science, climate policy and the future of Deep-Sea Mining into the same spotlight.

A new expedition led by international Researchers is returning to these abyssal plains to test whether metallic nodules really generate oxygen without sunlight, and what that might mean for Underwater Ecosystems on a planet already hungry for critical metals.

Dark Oxygen mystery in a deep-sea mining hotspot

In 2024, teams working in the Pacific and Indian oceans reported something that challenged textbook Oceanography. Instruments resting on the seafloor, thousands of metres down, recorded unexpected Gas Emissions of oxygen in zones where photosynthesis should be impossible.

How Rare Australian Rocks Trace the Birth of a Vital Metal

Bone Cancer Treatment Surprisingly Reduces Tumor Pain

The suspected source was the polymetallic nodules carpeting the Pacific’s Clarion-Clipperton Zone (CCZ), an area the size of continental Europe targeted by companies for Deep-Sea Mining. These potato-sized clumps are rich in cobalt, nickel and manganese, and their role in producing Dark Oxygen is now at the centre of a scientific dispute covered by outlets from ScienceAlert to Nature.

Life in the abyss and why oxygen matters

Even far from sunlight, abyssal plains host a surprising cast of life forms. Microbial mats coat sediments, while sea cucumbers, brittle stars and carnivorous anemones patrol the nodules, feeding on slow-falling organic particles from the surface.

For these Underwater Ecosystems to thrive, a steady supply of oxygen is needed. The new measurements suggest that Dark Oxygen might be sustaining local pockets of life, complicating assumptions that the abyss is a low-energy desert ready for industrial extraction, as discussed in reports such as New Scientist’s coverage of the CCZ.

How researchers will test the dark oxygen hypothesis

The new mission, supported by organisations including The Nippon Foundation and several universities, will lower custom-built deep-ocean landers to depths reaching roughly 10,000 metres. These frames, bristling with sensors, are designed to sit silently on the seafloor for days.

Led by marine ecologist Andrew Sweetman of the Scottish Association for Marine Science, the team aims to verify whether the previously reported oxygen signals truly come from the nodules, or from unnoticed artefacts. This careful approach responds directly to critiques documented in analyses by Scientific American.

Electrochemical rocks and tiny ocean batteries

One proposed mechanism sounds almost like alien technology, yet remains firmly grounded in chemistry. Layers of metals inside each nodule may act like a natural battery, generating an electric potential across their surface.

Measurements have found voltages up to about 0.95 volts on individual nodules. That is less than the 1.23 volts usually cited for splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen, but the researchers suspect clusters of nodules or micro-scale effects could push local conditions higher, especially under deep-sea pressure.

Inside the deep-sea landers and lab simulations

The landers carry optical oxygen sensors to track subtle Gas Emissions, as well as pH probes to detect tiny shifts in acidity that would signal electrolysis. If water is being split, protons released into the surrounding seawater should slightly lower the pH.

Alongside continuous measurements, automated corers will collect sediments and nodules. Back on shore, these samples will be analysed under high-pressure reactors that recreate the deep ocean’s crushing force, similar to experiments described in engineering-focused coverage by Interesting Engineering.

Microbial communities: batteries or passengers?

Each nodule may host up to 100 million microbes, forming intricate biofilms. Microbiologist Jeff Marlow’s team plans to use DNA and RNA sequencing, together with fluorescence microscopy, to identify which organisms occupy different layers.

The key question is whether these microscopic communities simply exploit the electrochemical environment, or actively shape it. Are they catalysing water-splitting reactions, or consuming the oxygen as fast as it forms, leaving only a narrow measurable imprint in the surrounding water column?

Scientific controversy, mining pressures and environmental impact

The debate over Dark Oxygen is not only academic. Companies exploring polymetallic nodules argue that previous measurements misinterpreted contamination from surface air. One industry-backed paper claimed there was not enough electrical energy within nodules to drive meaningful water electrolysis.

Sweetman’s group counters that their landers do not show similar oxygen signals in other regions, such as the Arctic seabed, and that new electrochemical data indicates water oxidation can occur at lower voltages on mineral surfaces. A detailed rebuttal is currently under peer review, while long-form investigations such as the Pulitzer Center’s reporting on the dark oxygen mystery explore how commercial funding shapes the discussion.

From seabed metals to climate and clean-tech on land

The CCZ alone is thought to contain enough cobalt, nickel and manganese to supply global battery demand for decades. Supporters of Deep-Sea Mining argue that harvesting nodules could accelerate the transition to electric vehicles and renewable energy storage.

If nodules prove to be active sources of Dark Oxygen underpinning fragile Underwater Ecosystems, any large-scale removal might alter deep-ocean chemistry in ways that are hard to reverse. Coverage from outlets such as ABC News and SciTechDaily has highlighted these possible Environmental Impact trade-offs.

Why dark oxygen matters for Earth and future exploration

Understanding how oxygen can appear in permanent darkness is more than a niche puzzle in Marine Biology. If mineral-driven electrochemistry or microbe–mineral partnerships can split water at depth, similar processes might operate on icy moons or ancient Mars.

For space agencies such as NASA and ESA, which plan missions to Europa, Enceladus and other ocean worlds, the CCZ becomes an analogue laboratory. Lessons from this Subsea Exploration could guide instrument design for future probes searching for energy sources that might sustain extraterrestrial life.

What you can watch for in the coming years

The unfolding story combines frontier science, industrial ambition and environmental ethics. The next data from deep-sea landers will not only test whether Dark Oxygen is real, but also influence how regulators such as the International Seabed Authority weigh extraction against conservation.

For readers following climate policy, ocean protection or the hunt for life beyond Earth, the outcome will help answer a deceptively simple question: when rocks start behaving like tiny batteries in the dark, how should humanity respond?

- Scientific stakes: Redefining oxygen cycles in the deep ocean and testing electrochemical life-support mechanisms.

- Environmental stakes: Assessing how mining nodules could disrupt habitats and long-term carbon storage on the seafloor.

- Technological stakes: Informing sensor design for subsea robots and future ocean-world missions by agencies like NASA and ESA.

- Societal stakes: Balancing clean-energy material demands with protection of barely known Underwater Ecosystems.

What exactly is dark oxygen in the deep sea?

Dark oxygen refers to oxygen detected in deep ocean regions where sunlight cannot penetrate and traditional photosynthesis cannot occur. In current research, the focus is on oxygen that seems to be produced near polymetallic nodules on the seafloor, possibly through electrochemical reactions or microbe–mineral interactions rather than by algae at the surface.

How are researchers testing whether nodules produce oxygen?

Scientists are deploying autonomous landers equipped with oxygen and pH sensors directly onto nodule fields in the Clarion-Clipperton Zone. These platforms record gas fluxes for days, collect sediment and rock samples, and allow teams to recreate deep-sea pressure and chemistry in laboratory reactors to see whether water can be split into hydrogen and oxygen under controlled conditions.

Why does dark oxygen matter for deep-sea mining plans?

If nodules help generate oxygen that supports local organisms, removing them at industrial scale could alter the chemical environment and reduce habitability for deep-sea communities. Regulators and companies must understand this potential environmental impact before authorizing large extraction projects targeting metals for batteries and clean-energy technologies.

Could the dark oxygen findings be an experimental error?

Some industry-funded scientists argue that earlier measurements may have been contaminated by air trapped in equipment or misinterpreted signals. The current expedition is designed specifically to address those criticisms, using improved lander designs, control sites, and independent lab tests to confirm whether the oxygen originates from the seafloor itself.

What is the connection between dark oxygen and astrobiology?

Ancient Giant Kangaroos Were Capable of Hopping After All

Stopping HIV in Its Tracks: The Century’s Most Innovative Breakthroughs

If mineral surfaces and microbes can generate oxygen in complete darkness on Earth, similar mechanisms might exist on other ocean worlds, such as Europa or Enceladus. Understanding these processes informs astrobiology by broadening the range of environments where chemical energy could sustain life beyond our planet.